A roast turkey dinner, 18th century style! This spit-roasted bird is stuffed with a tasty chicken forcemeat and served up with a rich white wine gravy, flavoured with anchovies, oysters, celery, mushrooms, artichokes and mace.

A Forc’d Turkey

Take a large turkey. After a day kild, slit it down ye back, & bone it & then wash it. Clean stuf it as much in ye shape it was as you can with forc’d meat made of 2 pullits yt has been skin’d, 2 handfulls of crumbs of bread, 3 handfulls of sheeps sewit, some thyme, & parsley, 3 anchoves, some pepper & allspice, a whole lemon sliced thin, ye seeds pick’d out & minced small, a raw egg. Mix all well together stuf yr turkey & sow it up nicely at ye back so as not to be seen. Then spit it & rost it with paper on the breast to preserve ye coler of it nicely. Then have a sauce made of strong greavy, white wine, anchoves, oysters, mushrooms slic’d, salary first boyl’d a littile, some harticholk bottoms, some blades of mace, a lump of butter roll’d in flower. Toss up all together & put ym in yr dish. Don’t pour any over ye turkey least you spoyl ye coler. Put ye gisard & liver in ye wings. Put sliced lemon & forc’d balls for garnish.

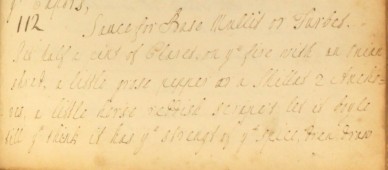

Bread Sause for Turkeys

Take stale bread & crumble it in as much water as will cover it. Shred a large onion in it & a little pepper, then give it a scald to heat & soften it. Then put as much cream as will make it very white, a little bit of butter, & set it over ye fire & let it stew, stirring it all ye while till you see it look thick & taste well.

How about some vegetables? This recipe for creamed celery would add a touch of indulgence to the meal:

Take your sallary and cut it small. Then boyle it tender in fair water. Then take it and stew it in fresh cream and a little nutmeg. And when it is so stewd, put in a little white wine and gravy and melted butter as you think proper, and so serve it up.

And here are two suggestions borrowed from the Regency cookery writer Dr William Kitchiner. Red beetroot will bring some colour to the plate, while ‘potato snow’ sounds fitting for a winter-time feast…

Red Beet Roots

Are dressed as carrots but neither scraped nor cut till after they are boiled. They will take from an hour & half to three hours in boiling. Send to table with salt fish, boiled beef &c.

Potato Snow

The potatoes must be free from speck[s] and white. Put them on in cold water. When they begin to crack, strain them and put them in a clean stewpan by the side of the fire till they are quite dry and fall to pieces. Rub them thro’ a wire sieve on the dish they are to be sent up in, and do not disturb them.

Merry Christmas to all of our Cookbook followers! xxx