‘Dutches of Cleaveland’ Pancakes versus Pancakes and Fritters

Christina and David were once again the willing volunteers who joined Kim and Trish for our seventh cooking challenge. And what better way to celebrate Shrove Tuesday than with a cook-off with two unique takes on the classic pancake.

The Duchess of Cleveland’s pancakes

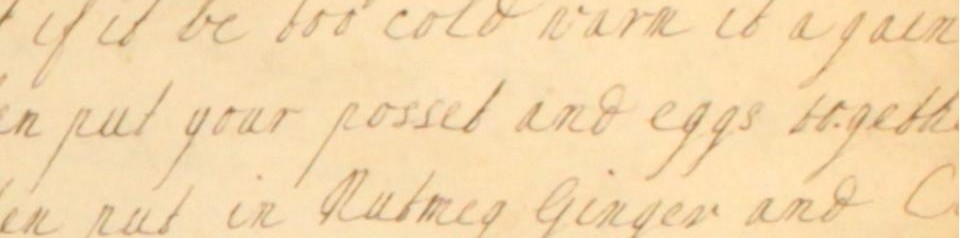

Beginning our pancake cook off with a recipe for the ‘Dutches of Cleaveland’ pancakes, we were struck by the quantity of eggs and butter involved – eight eggs in one batter? The quantities were overwhelming! We decided to downsize the recipe, roughly halving each of the quantities. While we beat up the batter, David regaled us with tales of the Duchess of Cleveland, Barbara Villiers; a Catholic who maintained an infamous relationship with Charles II as his mistress from 1660 to 1668.

Getting busy with the batter for ‘Dutches of Cleaveland’ pancakes

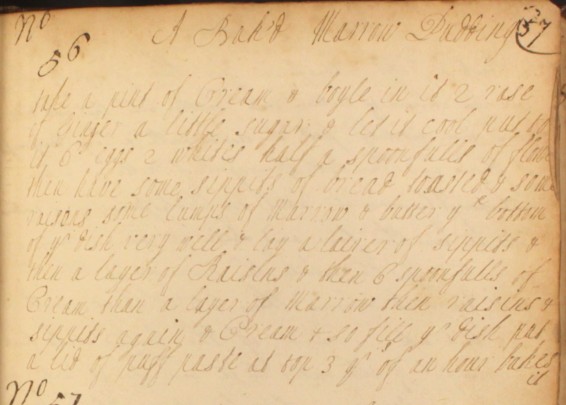

We mixed the batter thoroughly; David expertly folding the butter into our mixture. With this completed and our pan heated, Trish was given responsibility for flipping our pancake. Our first attempt stuck stubbornly to the pan, even though there was a good deal of butter in the mixture. We were dry frying the batter as the recipe suggested, but it seemed to be ruining our chances of getting the perfect pancake flip! Thankfully, things got better… the second and third batches were easier to cook now that the pan had been ‘seasoned’ by our first fritter.

As the pancake was cooking, Christina remarked that neither of our recipes made no mention of lemons or oranges – nowadays we are so used to having pancakes served up with a squeeze of lemon juice a little grate orange zest. We had a chat about our expectations, all agreeing that it was easiest to picture the end result when we could compare the Georgian dishes to a modern day equivalent. David, however, raised the point that the modern pancakes were were used to would inevitably colour our opinion of these historical recipes.

Our Duchess of Cleveland pancakes turned a lovely golden brown but proved difficult to flip!

Chatting over, it was time for the tasting! The pancake looked appetising but, served up on its own, it was not sweet enough for us. David compared it to a ‘mini Yorkshire pudding’ in both taste and texture, and wondered whether this was now what we’d regard as a pudding pancake. We were glad that no additional butter had been added to the pan as the result was rather oily.

Furthermore, with no definite measure of nutmeg in the recipe we felt this flavour was a little muted in this first attempt. Were our palates missing the stronger flavours of perfumed rose water from other recipes?! We decided to add an additional sprinkle of nutmeg to each subsequent batch of batter we cooked, and with some success: it considerably enhanced the flavour.

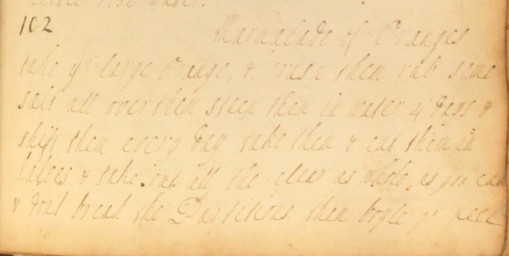

Pancakes and Fritters

Our 19th century style pancake on the stove

Our second batch of pancakes was inspired by a 19th century recipe with the title ‘Pancakes and Fritters’, sourced again from our Cookbook of Unknown Ladies. The recipe allowed a ‘walnut’ of butter to be used in the pan, but contained no butter in the actual mixture. Our pancake flipping was eased by this additional butter – Trish making many successful flips – but unfortunately the end result was a much drier affair and almost rubbery in texture. We added sugar and lemon to this round of pancakes to enliven the taste and bring our own traditional view of pancakes into the mix.

We turned our 19th century style pancake into something more familiar to our palates by adding a sprinkling of lemon juice and sugar

With pancakes such a well-loved treat in Britain today, our Unknown Ladies had a lot to live up to. Our Cooking Up History group enjoyed comparing our recipes with the pancakes we’ve re so used to today. Although both recipes had their pros and cons, we definitely felt the second batch of ‘Pancakes and Fritters’ was the more successful of the two. If you’re tempted to have a go at the Georgian pancake challenge, try out one of our recipes today!