Despite the current culinary revival of using offal and cheap cuts of meat, there are some recipes in our Cookbook of Unknown Ladies which only the most adventurous of cooks are likely attempt today.

Among these intrepid cooks is historical food expert Annie Gray, who gave nineteenth-century cow heels a try.

A nineteenth-century recipe for fried cow heel, from The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies

Cow Heel

This will furnish several good meals. When boiled tender, cut it into handsome pieces. Egg and bread crumb them, fry them a light brown, lay them round a dish and put in the middle sliced onions, fried.

The heel ready for boiling

Annie boiled the cow’s heel with a little carrot and leek to add flavour to the stock. Once cooked, she chopped the heel into pieces and coated them in breadcrumbs before frying up the whole lot in a deep pan of oil.

Once fried and drained of excess oil, the cow’s heel is ready to serve

What did she make of them?

“It was not vile. Indeed, at first, they were rather pleasant. I would say that deep fried pigs’ ears, which are beginning to appear more and more on menus now, are better, as they have more crunch. These are a bit more gooey, and you do need to like the taste of cow – pork, I think, is a bit more accessible. As a starter or snack, they’d be great”

Annie served her cow’s heel with cream and horseradish – a popular Georgian accompaniment. Alternatively, you could try it with ‘Mr Kelly’s Sauce for Boiled Tripe, Calf Head or Calf Heel’:

Garlick vinegar, a tablespoonful – of mustard, brown sugar & black pepper, a teaspoonful each stirred into half a pint of oiled melted butter.

Like many Georgian and Regency dishes, cow heel was highly economical to prepare. The stock formed when boiling the heel could be used to make jelly, and whole of the boiled heel could then be eaten, skin and all, with no waste.

If you take a liking to cow’s heel, you can even serve it as a sweet dish! In the following eighteenth-century recipe, the boiled heel is finely chopped and added to a fruited suet pudding mix:

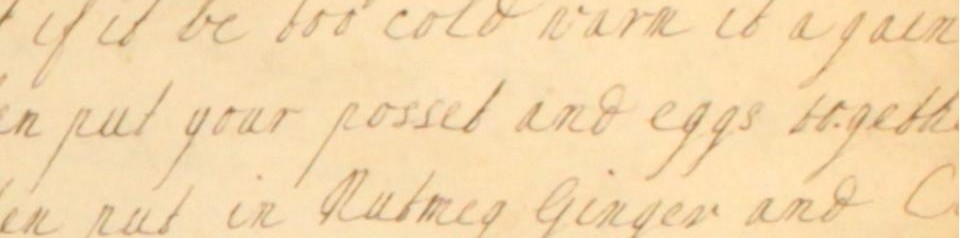

Neat’s foot pudding, made with cow heel, from The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies

To Make a Neat Foot Pudding

Let your feet be well boyled. Take half a pound of them chopd small, half a pound of beef shuit, half a pound of currants, four eggs well beatten, some sugar, three or four spoonfulls of flower, salt, sack, brandy and nutmeg. Mix all to gether. An hour will boyle it.