Archivist Jo Buddle explores the extraordinary story of a giant plum pudding and reveals the darker reality of life in Britain’s Victorian workhouses:

This image from the Illustrated London News of 3 January 1863 records a ‘monster’ undertaking at Marylebone Workhouse. It shows a plum pudding being made by the London United Cooks’ Society for cotton workers in Manchester, who were struggling with supply because of the American Civil War. The Marylebone Union lent their boiler and facilities for the job

This was no ordinary plum pudding. The finished pudding was over 10 ft in circumference and the list of ingredients was breathtaking. It contained 130 lb of currants, 130 lb of sultanas, 210 lb of flour, 130 lb of suet, 80 lb of peel, 80 lb of sugar, 1040 eggs, 8 gallons of ale, 4 lb of mixed spice and 1 lb of ground ginger. The final result weighed in at 900lb!

The kitchens at Marylebone Workhouse were well set up for mass catering. At its height, Marylebone workhouse had capacity for 1921 inmates. Its dining room was was 120ft long and the kitchen was equipped accordingly, with two 50 gallon beef-tea boilers and a 200 gallon tea infuser. The potato steamers had a total capacity of three quarters of a ton.

On occasion, at Christmas, inmates at Marylebone might be granted a special meal by the workhouse guardians, supplementing their regular meagre diet with a festive cake or pudding. The usual fare at Marylebone was much more simple, featuring cheap dishes such as pea soup, mutton broth and Irish stew. Food was simple and strictly rationed.

This view of St Marylebone Workhouse was originally drawn by a pauper inmate of the institution in 1866.

Although the Marylebone workhouse did not rank amongst the severest of the poor house institutions, life within it was nevertheless hard and uncomfortable. Those who had lost the means to house and feed themselves turned to the shelter of the workhouse as a very last resort. Men, women and children were segregated and those who were able were expected to work for their living. All able inmates were employed in menial tasks, from stone-breaking to oakum-picking (unravelling old ropes, which would then be sold on to the Navy).

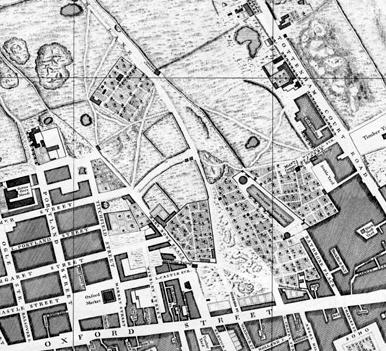

Plan of St Marylebone Workhouse in 1881, showing the separation of male and female dormitories (wards)

In some workhouses, the regime descended into cruelty. Rather than providing a living for inmates, the imbalance of exacting physical labour and a nutritionally-poor diet at these institutions was leading to starvation and death. In 1845 a scandal broke out at Andover, where workhouse inmates were found gnawing on animal bones due of a lack of food.

The work of high-profile campaigners such as Charles Dickens, along with news stories such as the scandal at Andover, led to a growing unease about the workhouse system. By late 19th century it was recognised that the dietary regimes of the nation’s workhouses had to change. From 1900 onwards, workhouse unions were encouraged to provide a more varied and balanced diet for their inmates. In 1901, the distribution of an official workhouse recipe book by the National Training School of Domestic Cookery ensured that workhouse kitchens were producing better meals with greater nutritional value.

In 1930, the system of poor law administration changed and, with the abolition of the Board of Guardians, many workhouses closed or became public assistance institutions. However, many people consider that workhouses didn’t truly disappear until the establishment of a Welfare State and the foundation of our National Health Service in 1948.

[Jo]