Our Cooking Up History volunteers returned to the Archives kitchen at the end of June to try out some more recipes from The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies. And how better to celebrate the onset of summer than with a table laden with lemon creams, Savoy biscuits and a jug of refreshing spring fruit sherbet?

We were all excited about the menu, and pleased to find we were starting to become familiar with the tastes of the Georgian period. As Christina set to work zesting the lemons for our ‘lemmond cream’, she remarked how popular citrus seemed to be with the Cookbook’s compilers. In the early part of the 18th century oranges and lemons were still relatively expensive, and it is unlikely that our unknown ladies had their own orangery or glass-house where the fruits could be grown. We can only assume that their household brought in enough income to allow them the luxury of lemons in their puddings!

Christina zests the lemons for our “lemmond cream”

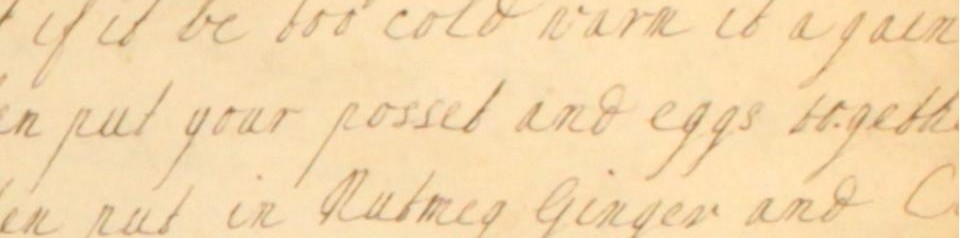

“Lemmond Cream”

Our first recipe sounded rather appetising: a refreshing mix of lemons, sugar and eggs would go into making our Lemmond Cream. It was quick and easy to make up the mixture, although we all observed that it took much longer to thicken on the heat than we’d anticipated. Perhaps this was a touch of 21st century impatience coming into play?

Thickening up the lemon cream on the hob

The end result was a sweet-smelling and “extremely strongly flavoured” dish which defied all the expectations the name had given us. A splash of orange flower water lent the creams a highly-perfumed flavour, but the appearance was rather less appealing. We’d all expected a light creamy colour, but they actually turned out a rather lurid yellowy brown! Maybe the long process of thickening the mixture on the stove had led to the sugar caramelising a bit. The texture looked a little grainy but was in fact very smooth to the taste.

Our “lemmond cream”!

On balance, we all quite liked the creams, but a few felt the flavours were a little on the over-powering side. David, on the other hand, could have done with even more of a punch: he felt that by straining the mixture and removing the zest we’d lost a strong element of our ingredients, which could have provided added layers of extra texture and taste.

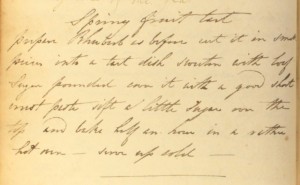

“Spring Fruit Sherbet”

Kim had prepared the Spring fruit sherbet earlier on in the day: an infusion of rhubarb, water, lemon and sugar syrup. It had been cooling in the fridge for some five hours by the time we came to try it.

The spring fruit sherbet went down well with some…

Everyone admired the pretty pink colour of the drink – a bit like pink lemonade or a summery Pimm’s punch – but its taste really divided opinion. Some were extremely keen. Georgina felt the blend quite purifying whilst David claimed it to be ‘very tart’ – not necessarily a bad feature in David’s opinion! And Kim was at the other end of the scale, needing to add extra sugar to her glass as it was far too bitter for her. Angela stood somewhere in the middle on all this, finding it not bad at all, but wondering whether a more dilute version might be better.

“Savoy Biscuitts”

The Savoy biscuits were the highlight of our afternoon’s cookery escapades.

Placing the Savoy biscuit batter on the floured trays

The method was easy to follow. David commented that these biscuits seemed likely to have been made in large volumes, although following the extremely lengthy whisking of our eggs we questioned how easy this method would have been for a greater quantity in a Georgian household. Today we would normally have resorted to an electric beater but perseverance by Angela and a fork eventually paid off to give us the desired soft peaks!

Angela drew the short straw of whisking the egg whites and sugar

The biscuits took 20 minutes in our electric oven and were very aesthetically pleasing, with a light brown colour. This, combined with the soft and slightly chewy meringue texture, meant they went down really well with all of the team.

The recipe specified that these biscuits would be “proper with tea in an afternoon” and so we popped the kettle on and enjoyed a good brew. A relief to Kim, who had been less than keen on the spring fruit sherbet!

Savoy biscuits, lemon creams and spring fruit sherbet: our Georgian-style spread!

What a lovely afternoon! David and Christina both commented how well everything had turned out, and what a nice spread it had been. A proper summer tea, which was certainly well-deserved by our Cooking Up History team!

“Cheers to a wonderful afternoon!” Our Cooking Up History group raise a toast with a glass of rhubarb sherbet

Fancy having a go at these recipes at home? Visit our Cooking Up History section for all the details!