Saffron is the dried stigma of the autumn-flowering crocus sativus (saffron crocus). This plant was widely cultivated in early modern England, and its historic importance is recorded in several place names in the south-east of the country. Saffron Hill, near Farringdon, once formed part of an estate that grew crocuses for saffron. Croydon’s connection with saffron goes back to Saxon times and is commemorated in its name, croh meaning crocus or saffron, and don meaning valley.

Saffron Walden became one of the foremost saffron farming and trading centres of Tudor and Stuart England, thanks to its light, chalky soil that could sustain large crops of crocuses. The streets of Saffron Walden were said to turn blue with petals during the saffron harvest, which took place between October and December.

By the early 18th century, the saffron industry was in decline. While harsh frosts in early autumn could effectively wipe out the English harvest, improving trade routes enabled merchants to import the spice from more reliable climates in Southern Europe. Imports in other spices and flavourings were also changing English tastes. Exotic products such as chocolate and vanilla contributed to the demise of saffron’s popularity in English kitchens.

Our Cookbook‘s recipe for saffron cakes favours English saffron over the imported spice, although by this time the country’s saffron trade was on the wane.

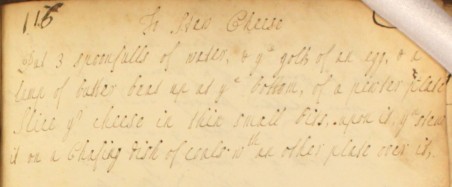

18th century recipe for making saffron cakes ‘as ye woman at the Blew Peel does’. Extract from The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies

To make saffron cakes as ye woman at The Blew Peel does (modernised spelling)

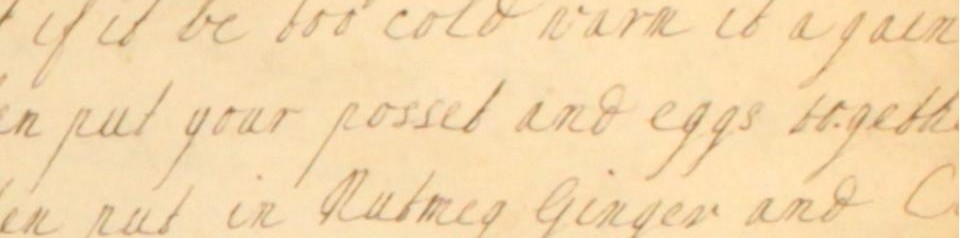

Take 6 quarts of flower, dry it and sift an ounce and a half of caraway seeds [and] 3 quarts of a pound of loaf sugar. Rub in[to] it a pound of butter. [Take] half an ounce of good English saffron dried and powdered very fine, steeped overnight in half a pint of milk; 12 eggs, beat their whites to a curd and mix the yolks with your saffron and milk, and set it over the fire. Stir a little more milk in it. Let it be just blood warm. Make a well in the middle and pour in your milk and whites and strain in half a pint of good barm. Work it up lightly to a paste [so] that it may be smooth. When you make your cakes, pat them with the palm of your hand. Prick them as they go into the oven, which must be very hot, cleaned out with a wet malkin.

—

Where was the ‘Blew Peel’, where this recipe is said to have its origins? We’ve found no reference to a pub of this name in the London area, nor to any of the obvious variations of this name (Blue Peel) etc. Could the recipe have travelled to our cookbook writers from another part of the country – maybe from as far as Devon or Cornwall, where the tradition of saffron buns is still strong today?

If you think you can help identify our mysterious ‘woman at the Blew Peel’, please get in touch!