This recipe for honey wine, or Irish sack, is among the earliest in our Cookbook. Water (river water) and honey are boiled and ‘scummed’ for three hours. Once cooled, the mixture is left for a couple of days until any solids have settled and the liquid can be poured off into a cask. And then there’s a further six months of brewing time until the wine can be finally bottled.

It is time-consuming, but simple, and the instructions are unusually thorough. There’s even a tip about stopping mice getting to the drink before you do!

A Receipt to Make Irish Sack

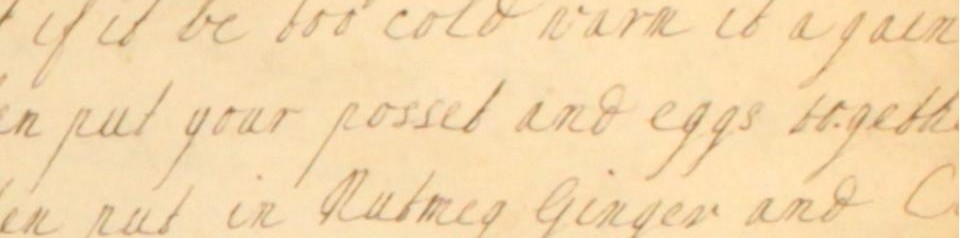

Take what quantity of river water you please. Mix honey with it till it will bear an egg [so] that the end appears a little above the water. Keep out a little of your liquor in a convenient pot or kettle, and as it boils up put in a little of your cold liquor to make the scum rise […] better and prevent its boiling over. Scum it clean and so continue to do for two hours as the scum rises. Then boil it another hour, having put in all the cold liquor, and keep it constantly scumming as you see occasion. When boiled, put into a clean wooden vessel in a cool place & let it stand [for] two days. [Separate] it […] from the settling and [put it in a cask]. Keep some of it in a black glazed crock covered with a pewter dish to fill up your vessel as it shrinks, & you must skim of [the] scruff that rises on the top of your vessel with a spoon, and so do till no more rises, keeping it constantly filled up as you find occasion. Keep your vessel covered with a clean slate or thin stone to keep out mice, but not too close as when you stop it because, if it has not air, it will work over and waste. It will be six months, or near it, before you can stop it up. When it is [a] year old, bottle it and put into every bottle 3 [stoned raisins]. Cork up the bottles.

No cold liquor to be put in the third hour. It will waste a third part in the boiling.

—

Of course, if you do decide to try this one at home, please don’t use river water. Tap water may lack a little in authenticity, but is a much safer option!

And here’s a quick 19th century tip on sealing bottles, passed down from Kitchiner’s Cook’s Oracle:

To Make Bottle Cement

½ lb black rosin, same of red sealing wax, quarter oz of bees wax melted in an earthen or iron pot. When it froths up, before all is melted and likely to boil over, stir it with a tallow candle, which will settle the froth till all is melted and fit for use.