Fine Sevil oranges, fine lemon, fine;

Round, sound and tender, inside and rine

(An old street cry of London)

Seville oranges have been a familiar taste in English cookery since the late Medieval period. But it wasn’t until the mid 17th century that sweet oranges, commonly known as ‘China oranges’, became part of the English culinary landscape. Their sweet flesh contrasted pleasingly with the better-known bitter oranges of Spain, and they quickly became popular.

Nell Gwyn (c1651-1687). Image property of Westminster City Archives

Bitter and sweet oranges were widely available in London from the late 17th century onwards. Nell Gwyn famously sold oranges at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane before taking to the stage, and orangeries sprang up at aristocratic houses across the country. By the time our ladies were compiling the Cookbook, oranges were being grown in glasshouses on many landed estates.

Despite their popularity, oranges remained expensive and were regarded as a delicacy. The authors of our cookbook’s recipes are careful to avoid any unnecessary waste. In this one for orange jelly, both the flesh and the zest are used:

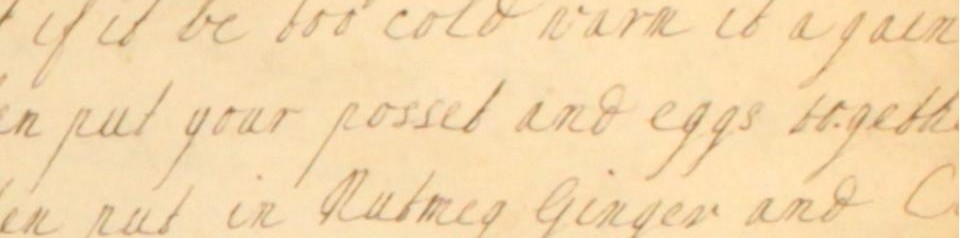

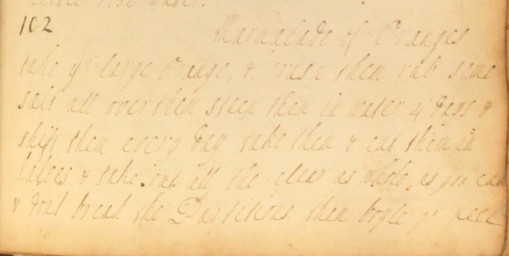

An eighteenth-century orange jelly recipe from the ‘Cookbook of Unknown Ladies’

Making Mrs Bracken’s orange jelly (modernised text)

Grate the rind of 2 China oranges, 2 Seville oranges, 2 lemons. Put it in to steep in the juice of 9 Seville oranges. Put half a pound of fine sugar, a quarter of a pint of water. Boil it to candy. When almost cold, mix the juice with 2 ounces of isinglass well boiled in a quart of water. Leave it till it is mixed. Then, mix it all together and strain it. Stir it till almost cold, then fill your moulds. You may add the juice of lemon or China orange if you like it.

—

Mrs Bracken uses Isinglass as the jelly’s setting agent. Derived from fish bladders, it has fallen out of common usage today, but is still sometimes used in viticulture to clarify wines. If you fancy making your own version of Mrs Bracken’s jelly, you might want to substitute it for gelatin.

The writer also asks you to boil the syrup to candy. 18th century cookbook writer Susanna MacIver says you can recognise this stages “by the sugar boiling thick like pottage” (Cookery and Pastry, 1789 p.205)

The recipe gives us our first clue as to the social circle in which our unknown cookbook writers were living in. We don’t know whether Mrs Bracken was a fellow domestic servant, or a well-known local cook, but she is our first named reference in our search for the identity of our mystery recipe writers…

Fancy giving this orange jelly a go? If you do, make sure you let us know how you get on!