“[Mince pies are] as essential to Christmas as pancake to Shrove Tuesday, tansy to Easter, furmity to Midlent Sunday or goose to Michaelmas day”

Lionel Thomas Berguer in The Connoisseur (1754)

—

The traditional Easter dish ‘tansy’ has largely been forgotten today, but for the Georgians it was as integral to the Easter festival as mince pies were to Christmas.

Members of the Tansy family, including common tansy (fig 11680) from J.C. Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of Plants (1828)

The dish takes its name from the tansy flower, tanacetum vulgaris, the bitter flavour of which was a reminder of the bitter herbs (maror) eaten by Jews at Passover. In our recipe, tansy leaf extract is combined with spinach juice and then added to beaten egg yolks, sugar and naple biscuits. Cream, nutmeg, sack and rosewater are all and added to the mix before being put over the fire to cook.

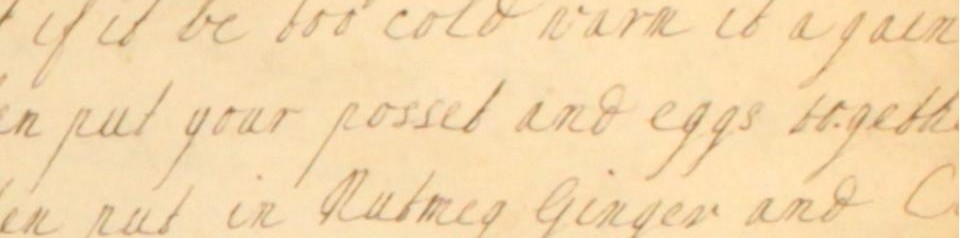

To Make a Tansy – Mrs Hayne’s Way (modernised spelling)

Take 12 yolks of eggs and beat them very well. Put half a pound of naple biscuit, a quarter of a pound of white sugar, a pint of spinach and tansy juice, a quart of cream, a nutmeg […] into a gill [¼ pint] of sack, the same of rose water. So, beat it up, put it into a skillet and put it over the fire till it is thick. So put it in the pan and fry it.

The result: a sweet, green-coloured omelette with the bitter undertone of tansy.

As time went on, the term ‘tansy’ was applied to a whole range of egg-based dishes, whether they contained tansy juice or not. One such recipe is a fruit fritter known as ”apple tansies’. We’ll be trying that one out later in the year…