We’d been hoping for a sunny day for our latest Cooking Up History session. With a summery menu of salmagundi salad and lemon-scented cheesecake on the menu, we were all set for a picnic-style celebration. As it turned out, the British Summer caught us out. But no matter – despite the grey skies there was plenty of cheer in the Archives Centre kitchen as we welcomed back our volunteers to try out more recipes from The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies.

‘Salamon Gondy’

Making up our first dish, the so-called ‘salamon gondy’, turned out to quite an entertaining experience. Our lengthy list of ingredients seemed fairly formidable, comprising fish, turkey, onions, beetroot, capers, gherkins, apple, boiled eggs and celery. The method was, by contrast, incredibly simple: chop and slice our ingredients into small pieces, then make up a basic vinaigrette as a dressing.

Kim assembling the salmagundi salad

Assembling our dish was the most technically challenging and exciting aspect of the recipe. We knew that colourful salads like this would have been carefully arranged to form eye-catching centrepieces for the Georgian dining table, and wanted to make sure that our version made a similarly striking impression. We discussed how best to arrange our ingredients, and checked out a few examples of similar salads online – not least Revolutionary Pie’s impressive version. Inspired, we set about constructing our spectacular salad.

The finished ‘salamon gondy’!

We were all very pleased with the finished design, a brightly coloured array of ingredients positioned in rings around the central portion of turkey breast. Archives staff member Hilary joined us for the tasting. She, along with the rest of the team, found much to be enjoyed in this eclectic salad, and thought it would make a great centrepiece at a special dinner today. Christina added that she ‘wouldn’t be ashamed to have it on my own table’.

Some of us had been a bit nervous about trying the salad, as the prospect of turkey mixed with salty fish and sweet apple and beet was something of an unknown quantity. For some of us, the tastes were to be a completely new experience – Rachel, for one, had never tried herring before.

Time for the tasting! The salmagundi went down surprisingly well

In the end we were all pleasantly surprised, and our enjoyment of the finished dish matched the fun we’d had creating it. With so many different flavours, at first every mouthful we ate was very different from the last. But as we continued to taste it, the flavours merged well, with the salty anchovies offsetting the sweetness of the apple, and the turkey acting as a nice, neutral counterbalance to the punchy onion.

Of course, our unknown ladies’ version of the salad may have tasted quite different had they opted for ingredients that had been preserved in other ways. We’d chosen fresh beetroot, and anchovies and herrings in oil. If the 18th century cooks had instead gone for fresh fish or pickled beetroot, the final effect could have been quite different. As with so many of the recipes in the Cookbook, the vague listing of ingredients leaves room for interpretation.

Would we make it again? It was certainly one of the healthier recipes we’d tried from the Cookbook. Rachel found the combination of flavours and textures was actually quite modern – the sort of thing you’d pay an arm and a leg for at a swanky London café.

The Georgians may have been less concerned with the healthy attributes of the dish, but they did pay considerable attention to making sure each meal comprised a balanced selection of dishes. What better counterpart to a stomach-filling roast than a fresh, light salad? And, as Judith pointed out, the salmagundi was another example of how the 18th century cook could concoct something spectacular out of economical, everyday ingredients.

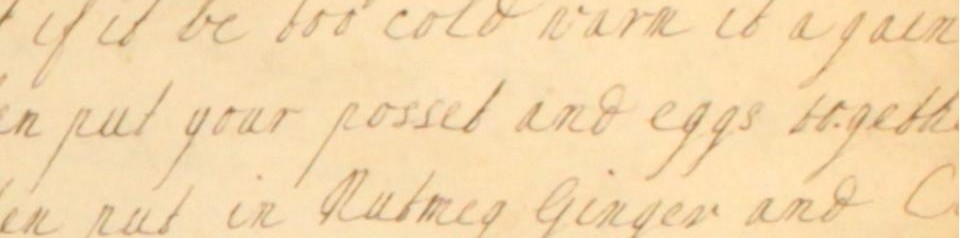

Lemon Cheesecake

Rachel prepares the lemon cheesecake batter – plenty of muscle work required!

We prepared a lemon cheesecake for second course, mixing together almonds, lemon, eggs and a large amount of butter. The recipe offered us the choice of adding either orange blossom water or rose water to our recipe. Rachel suggested that orange would enhance the citrus tones of the lemon, and Kim recalled how rosewater was sometimes pretty overpowering when we’d used it in other dishes, so we plumped for orange blossom.

Our lemon cheesecake

The finished cheesecake – so named because of its cheese-like-texture rather than any cheese in the recipe – delighted us all. Fresh out of the oven, it had an extremely pleasing appearance: a lovely golden brown with a firm consistency. The combination of citrus fruits was really delicious. Hilary enjoyed the subtle fragrance of our orange water with its ‘scented after-taste’ and Christina was so taken with it she said she’d bake the dish again at home.

Christina serves up the cheesecake for the all important tasting!

Previous dishes tried out by our Cooking Up History group, such as the almond puddings of our first session, had included so much butter that they’d been rather too rich for modern tastes. We’d feared something similar this time round, there being 220g to just 150g of almonds in the mix. But we needn’t have worried – the cheesecake wasn’t too rich at all.

Today we think of butter as a staple ingredient, and indeed it was too in the 18th century. But Rachel reminded us evidence that our Cookbook compilers churned their own butter. The effort that had gone into making their cheesecakes was therefore far more considerable than the 30 minutes it had taken to get our cakes in the oven. Food for thought…

Cooking success! Hilary, Christina, Kim and Rachel in the Archives Centre kitchen

If you’d like to give any of our recipes a go, check out our Cooking Up History pages!

[Kim]