Hot Spiced Gingerbread, sold in oblong flat cakes of one halfpenny each, very well made, well baked and kept extremely hot is a very pleasing regale to the pedestrians of London in cold and gloomy evenings. This cheap luxury is only to be obtained in winter, and when that dreary season is supplanted by the long light days of summer, the well-known retailer of Hot Spiced Gingerbread, portrayed in the plate, takes his stand near the portico of the Pantheon, with a basket of Banbury and other cakes.

Itinerant Traders of London (1804)

This ‘gingerbread man’ was one of over 30 street traders featured by William Marshall Craig in his book, Itinerant Traders of London. Craig himself seemed pretty impressed by the cakes, describing them as ‘very well made’ and ‘well baked’, and cheap at the price of a ha’penny.

We don’t know whether the unknown ladies of our Cookbook ever patronised this street trader’s stall at the Pantheon, but we do know that they were fans of gingerbread. They recorded two recipes for this spicy cake in their manuscript recipe book.

The first recipe comes to us courtesy of Mrs Ryves, whom we last met when she was making cream cheese. Here, we share her simple method for a classic gingerbread:

To Make Ginger Bread Mrs Ryves’ Way

Take two pound of fine flower, half a pound of white sugar, won ounce of pounded ginger all well dryed and sifted, a pound and a quarter of treacle, half a pound of fresh butter. Boyle the butter and treacle together then take it of and make it into a past with the things above nam’d and make it into what shapes you pleas. Butter your papers very well you bake them on. Your oven must be as hot as for Chease Cakes.

The second recipe is a little different from the gingerbread we’re used to today. Along with the ginger, caraway seeds and candied citrus are used to flavour the mix. It sounds rather intriguing… one to try as warming treat at tonight’s Bonfire Night celebrations? The mixture also contains eggs, so although our ladies make no mention of cooking, don’t forget to bake it!

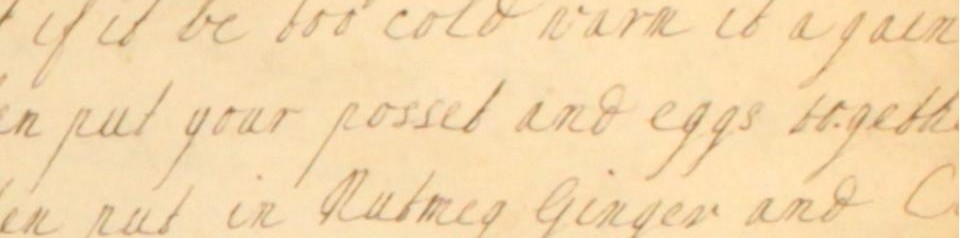

To Make Ginger Bread

Take fore qurts of flower, a pinte of treacle, & not quite halfe a pound of butter, four eggs, halfe an ounce of pounded ginger, halfe an ounce of carraway seeds, a qr of a pd of brown sugar, a nagin of brandy, som canded lemmon or orange. Mix all these in the flower. Melte the treacle & butter to geather. So mix all very well.