Chelsea and Christina were our willing helpers and ‘guinea pigs’ for the latest Cooking Up History session. They joined us in the Archives kitchen on a rather grey and damp autumnal day. It was perfect weather for sampling a seasonal menu of warm potato pudding and a warden pear pie, both 18th century dishes from our Cookbook of Unknown Ladies.

Potato Pudding

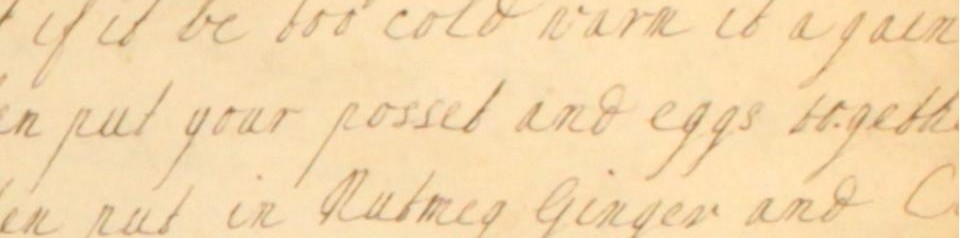

Potato pudding was a rather comforting prospect on a cold and damp Friday afternoon. Having peeled, boiled and cooled our potatoes in the morning, we were all set to combine our ingredients at the start of the session. Chelsea mashed our potatoes vigorously with a fork before adding the melted butter, cream and sugar. We then whipped up egg whites with a fork (foregoing the modern kitchen aid of an electric whisk) and added this to our mixture along with ground nutmeg, orange juice and a generous tablespoon of brandy. The pudding didn’t looking particularly appealing at this point but we were pleased that the method had been so straight forward. Happy that everything seemed to have gone to plan, we popped the pudding in the preheated oven.

Even though the unknown ladies’ recipe gave us a suggested cooking time for the pudding, there was no indication of oven temperature. We kept a close eye on it while it was cooking, removing it from the oven only to return it several times, until we were satisfied that it had cooked through. After 1 hour and 15 minutes of cooking time, and a further 10 minutes to allow the dish to cool and set, our patience paid off and we were able to sit down and enjoy the end result!

While Chelsea dished up, Christina remarked that the potato pudding seemed very similar in appearance to many of the other 18th century dishes we’d tried over previous sessions. Thinking back, we all agreed that many of the puddings we’d tried – from almond puddings to cheeseless cheesecakes – had a similar smooth consistency and golden colour. But each dish had something different to offer in terms of flavour, and we were sure that the potato pudding would be no exception…

In fact, it was delicious! The delicate flavouring of the nutmeg was particularly pleasant and, balanced by the brandy, was not overpowering. The potato provided a nice texture and we didn’t even mind the few lumps that had escaped Chelsea’s fork! Our conversation turned briefly to modern day equivalents of this dish, with Hilary noting its resemblance to semolina and Chelsea commenting on the similarities between our dish and sweet potato pie, a traditional dish from the American South.

Warden Pye

Our warden pie was keenly anticipated by the archives staff, all of whom wanted to try a piece of our fresh pear pie. For our Cooking Up History team, however, it was going to be one of their most technically challenging recipes to date.

The recipe had proved tricky to adapt for our modern kitchen, as it offered two separate methods for preparing the pears: either stewing them in water with alum, or baking them in a pot with white bread. Both methods were ways of softening the pears without them discolouring. We decided to part slightly from the original, poaching the pears and then dipping them in lemon juice to keep them from browning.

We did follow the recipe’s advice of peeling and coring the pears after they’d been cooked, but in hindsight we felt they would have been easier to handle had we done this before the poaching. It was a pretty fiddly job!

Having peeled and cored five of our six pears, we arranged them around the edge of our pastry-lined pie dish and stuffed each one with a colourful mixture of brown sugar, candied peel and cinnamon. We then peeled the remaining pear and placed it at the centre, scattering the remaining sugary stuffing mixture in the gaps between the fruits.

Finally, we placed a sheet of pastry over the top – with a steam hole cut around our central pear – trimmed down the edges and added a few pastry decorations. Chelsea commented that it all looked rather ‘fancy’!

Our Warden pie spent a good hour in the oven before we dished it up. The pastry had collapsed a little, but overall it looked incredibly appetising. A layer of sweet, juicy syrup had been created at the bottom of our pie, but we were all pleased to see we had not fallen into the trap of a Great British Bake Off style ‘soggy bottom’; our pastry was crisp all over. The cloves, one placed on top of each of our 5 stuffed pears, offered a stronger punch alongside the candied citrus fruits. None of the ingredients proved overpowering and we all agreed that the pie was well suited to modern palates.

We were really pleased that both of our recipes had been such a great success. Replete and enjoying a well earned rest, Chelsea mentioned that at the beginning of the session she hadn’t been able to envisage what our dishes would end up looking or tasting like. It is certainly true that the vague instructions given in many of our Cookbook’s recipes make it difficult to imagine the finished dishes. We noted the usefulness of visual imagery such as photos and drawings in contemporary recipe books. It’s a pity the lady compilers of our 18th century Cookbook hadn’t illustrated it with explanatory drawings and diagrams!

You can find recipes for both of these dishes in our Cooking Up History pages. If you try them out at home, don’t forget to let us know how you get on!