If you’re not a fan of Christmas cake or feel defeated by Christmas pudding, these 18th century plum cakes may be for you!

Plum cakes were often presented at Georgian celebrations, from weddings to Christmas feasts. These lightly-fruited sponges were not wildly different from everyday tea-time treats such as pound cakes and tea breads. However, for special occasions they would be decorated with icing and sweetmeats.

This recipe suggests making ‘little plumb cakes’ in individual tins or pans. Dividing the batter up into smaller portions does help to reduce the baking time, but the recipe nevertheless demands a great deal of stamina. For the required rise, the cake batter needs an hour’s beating before being baked in the oven:

These recipe should produce lovely lightly-fruited sponges – but you’ll need to beat the mixture an hour to get the desired effect!

To Make Little Plumb Cakes

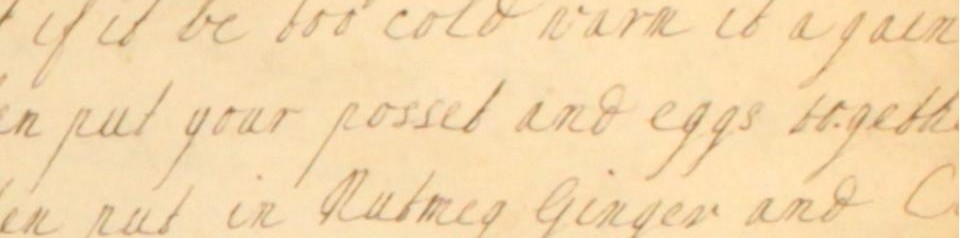

Take a pnd of flower well dryed, 1 pnd of butter & a pnd of currants well washed & pickd, 3 qrs of a pound of white sugar well sifted, six yolks and 2 white well beaten. Beat the butter with a little orange flower water with yr hand till it cream, then put in yr corrants & a whole nutmeg. Then beat it again. Then mix the flower & sugar & put it in by handfulls, till all be in. Keep itt beating an hour after and when the oven is hot, butter yr pans. Yr oven must be as hot as for cheesecakes.