A cold cream is a cooling ointment that is applied to the skin as a moisturising cosmetic and cleanser. In the 1920s and 1930s, celebrity endorsements of brands such as Pond’s and Elizabeth Arden led to a huge uptake in commercially-produced emollients, with the verb ‘to cold-cream’ entering common parlance around this time. Cosmetic manufacturers began to market their creams with a liberal sprinkling of glamour: as a Hollywood actress’s beauty secret, or as the preferred cosmetic of European royalty.

Adverts for cold creams were so prevalent in the first half of the 20th century, one would be forgiven for thinking that they were a relatively recent invention. Far from it! Cold creams had already been a staple of women’s cosmetic drawers for centuries, long before mass-production came on the scene.

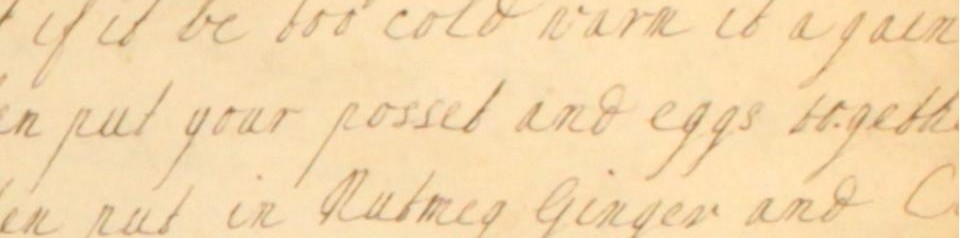

The ladies who wrote our Georgian Cookbook recorded this recipe for home-made cold cream, which they attribute to an ‘Aunt Preston’. With ingredients including trotter oil and spermaceti, a wax derived from the head cavity of the sperm whale, it’s a far cry from the glamorous image projected by early 20th century cold cream brands. On the other hand, its high fat content should have made it an effective moisturiser, and an effective defence against the harsh winter weather:

My Aunt Prestons Cold Cream

Half a pint of trotter oyl, 3 ounces of white wax, 3 quarters of an ounce of spermaceti, all put in to a silver vessel till melted. Yn put into an earthen pan & beat up wth water till it grows white & doos not stick to ye pan.