On Friday 1 March, ‘Cooking up History’ volunteers David and Angela joined us to whip up some dishes from the Cookbook of Unknown Ladies. Our Archives Centre kitchen was transformed with the sights and smells of the Georgian kitchen as we rolled up our sleeves, put on our pinnies, and got busy baking!

Our librarian Judith with Angela and David, the Cooking up History team!

We began the first in our series of historic cookery adventures with a selection of sweet recipes from the Cookbook: two 18th century recipes for almond puddings, and three buttery, boozy pudding sauces from the early 19th century. Perfect warming food to cheer us through the recent cold spell.

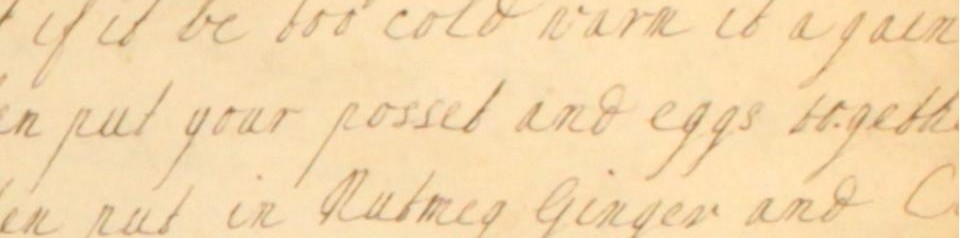

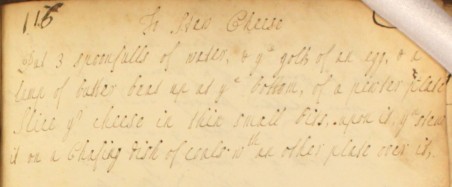

Our first challenge was to ‘translate’ the original recipes for use in our modern kitchen. Easier said than done. While the 19th century sauce recipes were pretty thorough, the earlier pudding methods were riddled with omissions! Filling in the gaps reinforced how these 18th century would have been been compiled by an experienced domestic cook, who was well versed in basic cooking methods, and judged most quantities and cooking temperatures by their own experience of what ‘felt right’.

One of the original recipes we adapted for the cookery session

There were plenty of potential pitfalls to avoid. Both of the pudding recipes called for huge quantities of eggs, but as those used in the Georgian kitchen would have been much smaller, we needed to adjust the quantities accordingly. We had to decide on which ‘weight’ of cream to use (we plumped for double rather than single) and even what spirit to substitute for ‘sack’.

And inevitably, there were some pitfalls that we failed to dodge. Without any instructions about how mix our ingredients, our first pudding batter turned out extremely lumpy and rather grey. But some good old-fashioned elbow grease with a wooden spoon got it looking more the part, and disaster was narrowly avoided.

Cross-barring our first almond pudding – almost ready to go in the oven!

Once our puddings were snugly in the oven, we sat back with a cup of tea to reflect on how things had gone so far. We’d taken plenty of short cuts in recreating these recipes – such as using ground almonds rather than pounding them by hand – and Angela remarked how time-consuming these puddings would have been without all the kitchen aids we have today. This got us thinking about all the other difficulties that a Georgian cook would have faced.

Even getting hold of ingredients seemed to be easier today. We found nearly everything we needed at the supermarket, and the more exotic ingredients (mace, rosewater) we got hold of from our local Indian grocery. Whereas other recipes in the Cookbook indicate that our 18th century ladies would have sourced some of the ingredients from their smallholdings – eggs from their own hens, and milk and cream from a domestic cow.

The timer interrupted our chat and it was time to try the puddings…

Almond pudding in a pastry case: the first pudding we tried and tasted

As we cut into our first almond pudding, we realised that something had gone a little awry, as the mixture was still fairly sloppy, and wasn’t keeping its shape as we’d expected. On taste, though, it didn’t disappoint. David was the first to comment: “ This is delicious!”. Rosewater was the predominant taste, and the nutmeg came through well too. Angela was the first to remark that it ‘tasted of Christmas’, and funnily enough, we all agreed.

David gives almond pudding no. 1 the thumbs up!

The second pudding turned out like something between a bakewell pudding and a baked custard, and was literally oozing with butter. We’d used sherry in place of sack, which came through fairly delicately.

The second almond pudding – a cross between baked custard and bakewell pudding

Angela serves up our second almond pudding

The 19th century sauces were less subtle. ‘Pudding catsup’ was rather heavily laced with sherry and brandy. The alcohol-free ‘Justin’s Orange Sauce’ was a bit more refined, and complemented rather than overpowered the puddings.

We were all surprised at how different these puddings tasted from the ones we are used to today. None of were used to using rosewater or mace in our day-to-day cooking, and the large quantities of butter in the recipes made the puddings seem incredibly rich to our modern palates. Nevertheless, we all felt we’d come one step closer to discovering the tastes of the Georgian kitchen, and to the lives our ‘unknown ladies’ would have lived.

To try out these recipes in your own home, take a look at our Cooking up History page, where we’ve published all of the recipes for your enjoyment!