The supermarkets are full of pumpkins for Halloween. If you’re not one for jack-o’-lanterns you can still join in the fun… Here are four tasty Regency dishes from our Cookbook of Unknown Ladies, all of them perfect for using up small pumpkins or squashes:

Gourds (or Vegetable Marrow) Stew

Take off all the skin of six or eight gourds. Put them into a stewpan with water, salt, lemon juice and a bit of butter or fat bacon. Let them stew gently till quite tender and serve up with a rich Dutch sauce or any other.

This recipe for Gourd Soup was transcribed into The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies from Kitchiner’s The Cook’s Oracle.

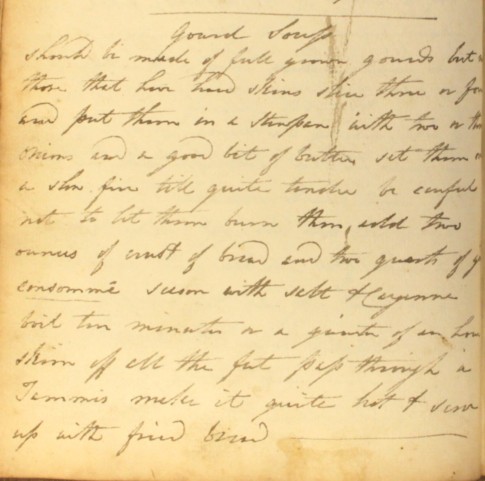

Gourd Soup

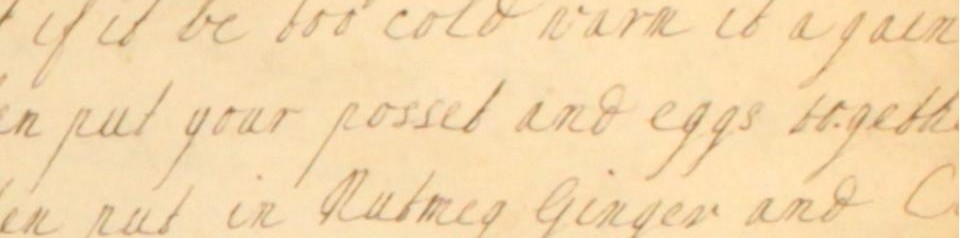

Should be made of full grown gourds but not those that have hard skins. Slice three or four and put them in a stewpan with two or three onions and a good bit of butter. Set them over a slow fire till quite tender. Be careful not to let them burn. Then add two ounces of crust of bread and two quarts of good consommé. Season with salt & Cayenne. Boil ten minutes or a quarter of an hour. Skim off all the fat, pass through a tammis. Make it quite hot & serve up with fried bread.

Regency recipe for fried gourds in breadcrumbs, borrowed from William Kitchiner’s Cook’s Oracle for the Cookbook of Unknown Ladies.

Fried Gourds

Cut five or six gourds in quarters. Take off the skin and pulp. Stew them in the same manner as for the table. When done, drain them quite dry. Beat up an egg and dip the gourds in it, and cover them well over with bread crumbs. Make some lard hot and fry them a nice colour. Throw a little salt & pepper over them and serve up quite dry.

These pumpkin slices are fried in hot lard and seasoned with salt and pepper: a tasty Regency treat from The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies.

Fried Gourds Another Way

Take six or eight small ones nearly of a size. Slice them with a cucumber slice. Dry them in a cloth and then fry them in very hot lard. Throw over a little pepper & salt and serve up on a napkin. If the fat is hot they are done in a minute and will soon spoil.